Derrida and Deconstruction

Derrida and Deconstruction

This blog is written as a task assigned by the head of the Department of English (MKBU), Prof. and Dr. Dilip Barad Sir. Here is the link to the professor's blogs for background reading: Click here to learn more about Derrida and Deconstruction & click here to read more about the Flipped Learning Network.

{getToc} $title={Table of Contents} $count={false}

|

| Jacques Derrida |

In this blog, you are invited to embark on a flipped-learning journey through seven foundational videos on Jacques Derrida’s deconstructive thought. By engaging first with concise video lectures on topics ranging from the elusive definition of deconstruction, Saussurean sign theory, and the pivotal notion of différance, to Derrida’s critique of structuralism, the rise of the Yale School, and the myriad ways other critical movements have integrated deconstructive strategies, you will arrive prepared to dive deeper. Rather than passively receiving content, you have already explored these concepts; here, we synthesize and organize them into an accessible, structured overview. As you read, consider how each theme interlocks—revealing language’s inherent instabilities, the play of meaning, and the perpetual self-critique at the heart of deconstruction—and prepare to apply these insights in our upcoming seminar discussion.

This blog features a concise summary and analysis of the full content, presented through videos in English, Hindi, and Gujarati. These were generated using NotebookLM.

⏬ English ⏬

⏬ Hindi ⏬

⏬ Gujarati ⏬

What is Flipped Learning?

Click here to learn more about what flipped learning is.

Video on Flipped Learning: In Search of Questions for Engaged Learning on YouTube/DoE-MKBU: Click here.

Video on Flipped Learning Task - Instructions on YouTube/DoE-MKBU: Click here.

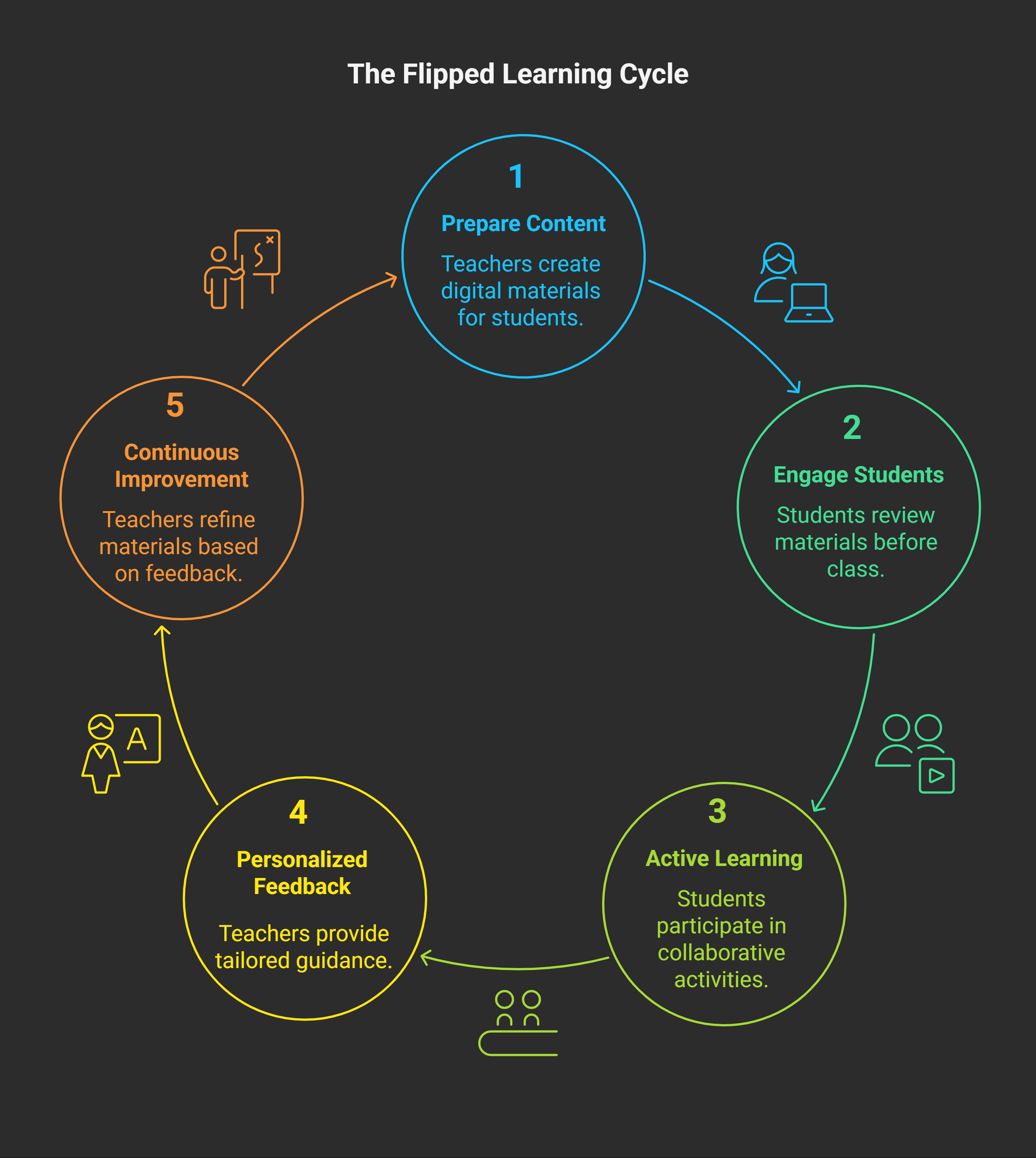

Flipped learning is a pedagogical approach that fundamentally reconfigures the traditional model of instruction by transferring the primary delivery of course content from the classroom to the individual learning space outside of class. In this model, students engage with preparatory materials—such as recorded lectures, readings, or multimedia presentations—prior to the scheduled class session. Consequently, classroom time is repurposed for active, collaborative activities that facilitate deeper understanding and application of concepts, thereby transforming the role of the instructor from a “sage on the stage” to a “guide on the side.”

At its core, flipped learning emphasizes active learning over passive reception. By requiring students to acquaint themselves with foundational content beforehand, the in-class environment becomes a dynamic arena for higher-order cognitive activities such as analysis, evaluation, and creative synthesis. This approach is grounded in constructivist principles, which assert that meaningful learning arises when learners actively construct knowledge rather than merely absorbing information. The shift to active learning enables students to take greater responsibility for their educational journey, fostering critical thinking skills and promoting independent inquiry.

Furthermore, flipped learning engenders a paradigm shift from a teacher-centered model to one that is fundamentally learner-centered. In this framework, the classroom is transformed into a space for exploration and application, where discussions, problem-solving exercises, and collaborative projects are emphasized. This reallocation of instructional time allows educators to provide targeted guidance and immediate feedback, catering to diverse learning styles and enabling differentiated instruction. The approach not only enhances individual engagement but also nurtures a supportive community where learners can collaboratively construct meaning.

Technology plays an instrumental role in the flipped learning model. Digital tools and online platforms facilitate the dissemination of course content, thereby increasing accessibility and allowing students to learn at their own pace. This integration of technology not only supports the acquisition of knowledge but also prepares students for a rapidly evolving, digitally interconnected world.

In summary, flipped learning represents a transformative approach that reallocates the traditional functions of classroom instruction. By shifting the emphasis from passive absorption to active engagement, it empowers students to construct their own understanding and develop a more personalized relationship with the material. This model champions a holistic, learner-centered environment that cultivates not only intellectual growth but also the practical skills necessary for lifelong learning.

1. Video 1: Defining Deconstruction

1.1. Introduction

Deconstruction, as conceived by Jacques Derrida, eludes definitive encapsulation. Rather than offering a fixed methodological blueprint, it instigates an ongoing interrogation of philosophical and literary foundations. This essay delineates its definitional complexity, clarifies common misconceptions regarding its negativity, and explicates the mechanism whereby deconstruction self-manifests within intellectual systems.

1.2. Definitional Complexity

1.2.1. The Limits of Rigorous Definition

Derrida consistently refuses to “define something once and for all rigorously,” insisting that every term—even “deconstruction”—resists a final, closed definition. This stance arises from his conviction that definitions invoke implicit hierarchies and exclusions, thereby concealing the very premises they presume to fix. Consequently, students and scholars seeking “clear-cut” terminology inevitably grapple with instability and aporia, for deconstruction foregrounds precisely those semantic fissures that defy terminological closure.

1.3. Deconstruction as Inquiry, Not Destruction

1.3.1. Beyond Negative Connotations

Contrary to widespread misunderstanding, deconstruction is not a destructive operation. Derrida expressly states it is “not a destructive activity” aimed at dismantling for its own sake; rather, it constitutes an “inquiry into the conditions” that enable—and simultaneously limit—philosophical systems. By examining the foundational assumptions of such systems, deconstruction reveals how binary oppositions (e.g., presence/absence) sustain and undermine themselves.

1.3.2. Transformative Ambition

Influenced by Heidegger’s “destruction” of ontology, Derrida seeks to transform Western thought’s structural paradigms. His correspondence with a Japanese translator underscores the challenge of conveying “deconstruction” across linguistic and cultural boundaries, further illustrating its inherently fluid, non-prescriptive character.

1.4. Autopoietic Mechanism

1.4.1. Différance and Self-Undoing

Central to deconstruction is the concept of différance, which denotes the simultaneous deferral and differentiation of meaning. The very “conditions which produce” a system—binary distinctions, hierarchical valorization—also generate the internal tensions that precipitate its deconstruction. Thus, deconstruction unfolds “on its own,” as the structural logic of any system contains the seeds of its own undoing.

1.5. Conclusion

Deconstruction, therefore, functions as both a mode of critical inquiry and a theoretical posture that refuses finality. By exposing the limits and blind spots of intellectual systems, it provokes a perpetual rethinking of foundational premises, encouraging a vigilant awareness of the provisional nature of all concepts.

1.6. Brief Answers to Key Questions:

1.6.1. Why is it difficult to define Deconstruction?

Because Derrida argues that defining any term “once and for all” enacts exclusions and conceals underlying assumptions; deconstruction itself reveals these semantic aporias, rendering fixed definition impossible.

1.6.2. Is Deconstruction a negative term?

No; it is not a destructive gesture but an “inquiry into the conditions” enabling—and limiting—intellectual systems, aimed at revealing and reconfiguring underlying premises.

1.6.3. How does Deconstruction happen on its own?

Through différance: the same binary distinctions that establish a system also generate internal tensions that self-deconstruct, making the process intrinsic to the system’s logic.

1.7. Question:

How does the interplay between différance and the archive complicate Derrida’s assertion that every philosophical system contains within itself the conditions of its own deconstruction, particularly when translating deconstructive concepts across disparate linguistic and cultural archives?

2. Video 2: Heidegger and Derrida

2.1. Introduction

Deconstruction, as formulated by Jacques Derrida, inaugurates a critical interrogation rather than a prescriptive method. It challenges the stability of conceptual oppositions and the very possibility of final definitions. From its origins in Heidegger’s “destruction” of ontology to Derrida’s own elaboration of différance, deconstruction reconfigures how Western philosophy understands language, presence, and foundation.

2.2. Heidegger’s Legacy

2.2.1. Destruction and Deconstruction

Heidegger’s Project: In 'Being and Time' (1927), Martin Heidegger “destroys” (“destruktion”) the history of ontology by interrogating the “question of Being.”

Derrida’s Translation: Derrida translates Heidegger’s German “destruction” into French as “déconstruction,” preserving the gesture of dismantling while emphasizing analysis over eradication.

2.2.2. Language and Decentering

Language Speaks: Heidegger later declares “it is language which speaks, not man,” decentering the human subject in favor of linguistic force.

Derrida’s Continuation: Derrida inherits this decentering, insisting that all meaning is produced through différance, the interplay of deferral and difference.

2.3. Rethinking Western Foundations

2.3.1. Metaphysics of Presence

Heidegger’s Critique: Western thought privileges presence—Being as immediate and self-evident—while repressing absence and becoming.

Derrida’s Extension: Derrida identifies “phonocentrism” and “logocentrism” as manifestations of this bias, arguing that privileging speech over writing conceals the play of trace and différance.

2.3.2. Reinventing Philosophical Language

Foundational Inquiry: Both thinkers seek to expose and transform the “hidden” premises of Western metaphysics.

Derridean Ambition: Derrida goes further by reimagining philosophical discourse itself, demonstrating that language structures both what can be said and what must remain unsaid.

2.4. Conclusion

Deconstruction emerges not as a fixed method but as an ongoing critique of foundational assumptions. Rooted in Heidegger’s “destruction” and propelled by Derrida’s différance, it perpetually unsettles binary oppositions, revealing that every system contains the conditions of its own undoing.

2.5. Brief Answers to Key Questions:

2.5.1. Influence of Heidegger on Derrida

Heidegger’s destruktion of ontology and his decentering of the human subject through language provided the conceptual impetus for Derrida’s own deconstructive framework.

2.5.2. Derridean Rethinking of Western Foundations

Derrida extends Heidegger’s critique by targeting logocentrism and phonocentrism, reshaping philosophical language to expose the inherent instability of meaning.

2.6. Question:

How does Derrida’s notion of différance problematize Heidegger’s destruktion when both gesture toward a dismantling of metaphysics, yet differ in their treatment of writing, speech, and the trace?

3. Video 3: Saussurean and Derrida

3.1. Introduction

Deconstruction, as reconceived by Jacques Derrida, interrogates Ferdinand de Saussure’s structural linguistics to reveal hidden instabilities within language and Western metaphysics. By juxtaposing Saussure’s notion of the arbitrary sign with Derrida’s concept of différance and Heidegger’s metaphysics of presence, one uncovers the subtle operations that both constitute and undermine systems of meaning.

3.2. Saussure’s Arbitrariness

3.2.1. Conventional Bond

Saussure asserts that the signifier (sound‐image) and the signified (concept) share no natural link: “sister” refers to its referent purely by social convention. Any word could denote any object, highlighting that meaning is arbitrary.

3.2.2. Relational Constitution

Meaning emerges relationally, through differences among signs (e.g., distinguishing “p” from “t”). There are no positive signifieds—each is defined negatively against others.

3.3. Derrida’s Critique of Arbitrariness

3.3.1. Infinite Deferral

Derrida contends that a word’s meaning is “nothing but another word.” The process of signification thus defers endlessly, destabilizing any fixed association and revealing arbitrariness as an unstable play of differences (différance).

3.3.2. Beyond Mental Locus

By displacing meaning from the mind to the network of signifiers, Derrida shows that conventions cannot fully ground signification, since each convention presupposes prior deferrals.

3.4. Metaphysics of Presence

3.4.1. Heideggerian Bias

Heidegger critiques Western thought’s tendency to equate Being with immediate presence (“this table is”). Presence is privileged linguistically through tenses (“is,” “was”) as proof of existence.

3.4.2. Logocentrism and Phallocentrism

Derrida extends this to logocentrism—privileging speech (presence) over writing—and phallocentrism, which privileges masculine presence. These biases encode social hierarchies (e.g., man/woman) into language itself.

3.5. Conclusion

By situating Saussure’s insights on the arbitrary, relational sign alongside Derrida’s notion of différance and Heidegger’s critique of presence, this exploration illuminates how language both constructs and destabilizes meaning. Saussure’s emphasis on convention and difference provides the groundwork; Derrida’s deconstructive move—revealing the endless deferral of signification and the hidden bias toward presence—unsettles any claim to finality. Together, they compel us to recognize that every act of interpretation is conditioned by prior linguistic structures and cultural presumptions. In doing so, deconstruction not only critiques inherited paradigms but also invites an ongoing, self-reflective interrogation of the very foundations of thought and language.

3.6. Brief Answers to Key Questions:

3.6.1. Ferdinand de Saussure's concept of language (that meaning is arbitrary, relational, and constitutive).

Meaning is arbitrary, constituted by social convention and defined relationally through difference.

3.6.2. How does Derrida deconstruct the idea of arbitrariness?

By showing that each signifier refers only to another signifier, Derrida exposes arbitrariness as an endless deferral (différance).

3.6.3. Concept of metaphysics of presence.

The bias that equates existence with immediate presence, privileged in speech over writing, underpinning Western logocentrism.

3.7. Question:

How does Derrida’s notion of différance both rely upon and subvert Saussure’s relational model, while simultaneously exposing the metaphysics of presence that Saussure’s framework inadvertently reinforces?

4. Video 4: DifferAnce

4.1. Introduction

Deconstruction, as theorized by Jacques Derrida, emerges from Ferdinand de Saussure’s structural linguistics and Martin Heidegger’s critique of ontology. Diverging from methodological prescriptivism, it interrogates how language’s arbitrarily constituted signs and entrenched metaphysics of presence generate—and simultaneously destabilize—systems of meaning. This essay elucidates three core aspects: Saussurean arbitrariness, Derrida’s deconstructive critique, and the metaphysics of presence underpinning Western discourse.

4.2. Saussure’s Arbitrariness

4.2.1. Conventional Sign

Ferdinand de Saussure maintains that the relationship between signifier (sound‐image) and signified (concept) is inherently arbitrary: a word like “sister” designates its referent purely by social convention, not natural affinity.

4.2.2. Relational Constitution

Meaning is relational, constituted by differences among signs (e.g., distinguishing “p” from “t”). Each sign’s identity arises negatively—defined by what it is not rather than by an intrinsic essence.

4.3. Derrida’s Deconstruction of Arbitrariness

4.3.1. Deferral and Differentiation

Derrida contends that signification perpetually defers meaning: a word points to another word, initiating an infinite chain of signifiers. This deferral undermines any fixed association, revealing arbitrariness as a dynamic interplay of difference (différance).

4.3.2. Destabilizing the Mental Locus

By displacing meaning from an idealized mental repository into a continuous play of signifiers, Derrida demonstrates that conventions cannot fully stabilize language; their inherent instability is constitutive rather than exceptional.

4.4. Metaphysics of Presence

4.4.1. Heideggerian Bias

Heidegger’s metaphysics of presence privileges immediate presence (“this table is”) as the criterion for Being. Presence is linguistically encoded through tenses (“is,” “was”), reinforcing an ontological bias.

4.4.2. Logocentrism and Phallocentrism

Derrida extends this critique to logocentrism—privileging speech over writing—and phallocentrism, revealing how Western discourse encodes social hierarchies by valorizing presence.

4.5. Conclusion

Through its engagement with Saussure and Heidegger, Derrida’s deconstruction unveils language as a site of both construction and subversion. By exposing arbitrarily constituted signs and the metaphysics of presence, it demands a perpetual rethinking of linguistic and conceptual foundations. This enduring tension between presence and deferral invites scholars to reconsider the possibility of closure in any theoretical system.

4.6. Brief Answers to Key Questions:

4.6.1. Derridean concept of Différance.

Différance denotes the twin processes of deferral (postponing meaning indefinitely) and differentiation (distinguishing signs by their differences). It is not a stable concept but a dynamic force that makes signification possible while continually destabilizing any claim to a final, present meaning.

4.6.2. Infinite play of meaning.

The infinite play of meaning describes how each signifier refers to another, ad infinitum, with no terminal signified. Every attempt to fix a word’s meaning merely defers understanding, generating a perpetual chain of signifiers. This reveals meaning as always “promised and postponed,” never finally present.

4.6.3. Différance = to differ + to defer.

Derrida’s différance fuses two senses of the French verb: “to differ” (distinguish) and “to defer” (postpone). The term’s unique spelling—indistinguishable in speech from différence—punctuates the primacy of writing over speaking and underscores how meaning both arises from and eludes the play of différance.

4.7. Question:

How does Derrida’s conception of différance—as both the force that defers meaning and differentiates signs—undermine the metaphysics of presence without reintroducing a covert telos or transcendental signified within the very play it seeks to disrupt?

5. Video 5: Structure, Sign, and Play

5.1. Introduction

“Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” marks a pivotal shift from structuralism to post-structuralism. Derrida’s 1967 essay interrogates the very foundations of structuralist thought, demonstrating how critique remains bound to inherited linguistic and philosophical assumptions.

5.2. From Structuralism to Post-Structuralism

5.2.1. Structuralism’s Dual Critique

Structuralism initially challenged both metaphysics and positivist science by exposing their hidden binaries. Claude Lévi-Strauss’s anthropological structures exemplified this, yet Derrida observes that these critiques nonetheless deploy the same underlying premises they seek to dismantle.

5.2.2. Inaugurating Post-Structuralism

Rather than outright rejection, post-structuralism “goes beyond” structuralism by revealing its inevitable self-contradictions. Derrida’s essay inaugurates this movement, showing that any theoretical system cannot escape the logic encoded within its own language.

5.3. Language and Internal Critique

5.3.1. “Language Bears Within Itself the Necessity of Its Own Critique”

Derrida’s aphorism captures the paradox that every linguistic statement carries a “blind spot”—an absence or lack—which demands continual interrogation. Since language encodes prior assumptions, critique can never fully transcend the tradition it inhabits.

5.3.2. Exemplary Recursions

Nietzsche/Heidegger: Nietzsche deconstructs metaphysics; Heidegger then labels Nietzsche “the last metaphysician.”

Derrida/Heidegger: Derrida critiques Heidegger as also bound by metaphysics.

Buddhism/Vedanta: A critique of Vedanta ultimately echoes Vedantic constructs.

5.4. The Play of Difference and Lack

5.4.1. Deferred Meaning

Following Différance, Derrida argues that ultimate meanings are perpetually “promised and postponed,” rendering any final interpretation impossible.

5.4.2. Autocritical Writing

Recognizing its own linguistic entanglements, deconstructive discourse remains autocritical, always questioning itself even as it questions Western tradition.

5.5. Conclusion

“Structure, Sign, and Play” demonstrates that critique and the critiqued are intertwined through language’s inherent lack. By exposing how any system invokes—and undermines—its own assumptions, Derrida establishes deconstruction as an ongoing, self-reflective dismantling of intellectual foundations.

5.6. Brief Answers to Key Questions:

5.6.1. Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences

Derrida’s essay inaugurates post-structuralism by demonstrating that structuralist critique of metaphysics and science unwittingly relies on the same linguistic assumptions. It reveals that no theoretical system can transcend its inherited language, thus “going beyond” by exposing the internal contradictions of structuralism itself.

5.6.2. “Language bears within itself the necessity of its own critique.”

This aphorism asserts that every linguistic articulation contains unacknowledged assumptions—a “lack”—that demand their own interrogation. Since critique employs the very language it examines, there is no external vantage point; deconstruction must remain perpetually self-critical and unable to achieve definitive closure.

5.7. Question:

In what way does Derrida’s insight that “language bears within itself the necessity of its own critique” destabilize the possibility of an external, foundational standpoint for knowledge, and how might this recursive self-critique avoid collapsing into nihilistic relativism?

6. Video 6: Yale School

6.1. Introduction

During the 1970s, Yale University’s Department of English became the epicenter of deconstructive criticism in America. Under the influence of Jacques Derrida, four scholars—Paul de Man, J. Hillis Miller, Harold Bloom, and Geoffrey Hartman—established what came to be known as the Yale School. Their work reframed literature as a site of linguistic instability, inaugurating deconstruction as a distinct mode of literary inquiry.

6.2. Historical Context

6.2.1. Continental Roots to Yale Vanguard

Before Yale’s embrace, Derrida’s post-structuralism had been largely confined to European philosophy. With deconstruction’s arrival at Yale, it broke into literary criticism, succeeding New Criticism and rapidly acquiring vogue status. The so-called “Yale hermeneutic mafia” transformed deconstruction from philosophical theory into a practical critical approach.

6.3. Core Characteristics

6.3.1. Literature as Rhetorical Construct

Yale deconstruction views texts as inherently figurative and rhetorical, exposing language’s unreliability. Metaphors like “somebody is an ass” engender ambivalence—literal or figurative—revealing that words generate multiple, often contradictory, meanings. This multiplicity undermines singular interpretation.

6.3.2. Critique of Formalist and Historicist Traditions

Rejecting both aesthetic-formalist and historicist-sociological readings, Yale critics argue that language never transparently reflects reality. Paul de Man’s notion of mistaking the materiality of the signifier (e.g., “red red rose”) for the signified emphasizes aesthetic illusion as a by-product of linguistic convention, rather than of social or historical context.

6.3.3. Romanticism and Counter-Conventional Readings

The Yale School’s preoccupation with Romanticism yielded revelatory, non-canonical interpretations. De Man demonstrated that allegory—more than metaphor—drives Romantic poetry’s epistemological gestures, producing undecidability between competing readings and exemplifying deconstruction’s “free play” of meaning.

6.4. Conclusion

By relocating deconstruction into literary studies, Yale critics demonstrated that texts are sites of perpetual autocritique, bound by the same linguistic structures they interrogate. Their legacy endures in contemporary criticism’s insistence on language’s inherent instability and the impossibility of final interpretation.

6.5. Brief Answers to Key Questions:

6.5.1. The Yale School: the hub of the practitioners of deconstruction in the literary theories.

The Yale School comprises Paul de Man, J. Hillis Miller, Harold Bloom, and Geoffrey Hartman, who, in the 1970s at Yale University, adapted Derrida’s deconstruction into literary criticism. They transformed philosophy’s abstract critiques into practical analyses, making deconstruction a central methodology in anglophone literary studies.

6.5.2. The characteristics of the Yale School of Deconstruction.

Key traits include viewing literature as inherently figurative, rejecting transparent aesthetic or historicist readings, and emphasizing multiplicity of meaning through rhetorical tropes. They focused on Romantic and canonical texts, unveiling undecidability and demonstrating that every critique remains bound to the same linguistic structures it interrogates.

6.6. Question:

How does the Yale School’s insistence on language’s figurative opacity reconcile with Derrida’s claim that deconstruction itself cannot escape its own linguistic conditions, creating a perpetual loop of critique and self-critique?

7. Video 7: Other Schools and Deconstruction

7.1. Introduction

Following Yale’s literary appropriation of Derrida, a diverse array of critical schools—New Historicism, Cultural Materialism, Feminism, Marxism, and Postcolonial Studies—have adopted deconstructive strategies to interrogate their respective objects of study. Rather than mimicking Yale’s rhetorical focus, these approaches harness deconstruction’s capacity to expose hidden assumptions, binaries, and power structures within texts and discourses.

7.2. Postcolonial Deconstruction: Dismantling Colonial Discourse

Postcolonial theorists deploy deconstruction “from within” to unmask the master narratives of empire. By demonstrating how colonial texts rely on binary oppositions (civilized/primitive, self/Other), they reveal the ideological underpinnings that sustain domination and enable their subversion.

7.3. Feminist and Gender Theory: Subversion of Patriarchal Binaries

Feminist critics use deconstruction to challenge the male/female dyad. By showing that gendered identities depend on mutually reinforcing oppositions, they destabilize normative phallocentric structures, opening space for non-binary and intersectional understandings of identity.

7.4. Cultural Materialism: Emphasis on Language’s Materiality

Cultural materialists emphasize Derrida’s insistence that language is a material construct. Analyzing how discourse encodes ideological programs, they reveal the economic and institutional forces that shape literary and cultural production, thereby aligning deconstruction with Marxist-inflected critique.

7.5. New Historicism: Text–History Reciprocity

New Historicists integrate deconstruction by treating history as textual and texts as historical artifacts. They demonstrate the reciprocal shaping of texts and contexts, showing how each historical narrative relies on linguistic structures that both enable and constrain meaning.

7.6. Marxist Engagement: Ideological Critique via Undecidability

Marxist scholars adopt deconstructive techniques to expose the ideological investments within economic and class narratives. By revealing the undecidable tensions between capital and labor discourses, they critique received economic truths as contingent and contested.

7.7. Conclusion

Across these schools, deconstruction functions less as a rigid method than as a critical sensibility: it persistently interrogates the linguistic foundations of meaning, power, and knowledge, enabling each discipline to uncover and contest its own blind spots.

7.8. Brief Answers to Key Questions:

7.8.1. How did other schools like New Historicism, Cultural Materialism, Feminism, Marxism, and Postcolonial theorists use deconstruction?

Other schools applied deconstruction to reveal hidden power structures within their domains: New Historicism exposed history’s textuality; Cultural Materialism highlighted language’s material and ideological dimensions; Feminism subverted gender binaries; Marxism deconstructed class narratives; Postcolonial studies dismantled colonial master-discourses, demonstrating how each relies on and can be undone by internal linguistic oppositions.

7.9. Question:

In what manner can deconstruction’s inherent self-critique reconcile the Marxist imperative for materialist totality with the postcolonial insistence on localized discursive difference without lapsing into an irresolvable theoretical aporia?

Additional Resources:

Video on Deconstruction I on YouTube/DoE-MKBU: Click here.

Video on Deconstruction II on YouTube/DoE-MKBU: Click here.

References

Barad, Dilip. “Deconstruction and Derrida.” Dilip Barad | Teacher Blog, 21 Mar. 2015, blog.dilipbarad.com/2015/03/deconstruction-and-derrida.html. Accessed 25 June 2025.

---. “Flipped Learning Network.” Dilip Barad | Teacher Blog, 24 Jan. 2016, blog.dilipbarad.com/2016/01/flipped-learning-network.html. Accessed 25 June 2025.

---. “Unit 5: 5.1 Derrida and Deconstruction - Definition.” YouTube, uploaded by DoE-MKBU, 22 June 2012, youtu.be/gl-3BPNk9gs. Accessed 25 June 2025.

---. “Unit 5: 5.2.1 Derrida and Deconstruction - Heideggar.” YouTube, uploaded by DoE-MKBU, 22 June 2012, youtu.be/buduIQX1ZIw. Accessed 25 June 2025.

---. “Unit 5: 5.2.2 Derrida and Deconstruction - Ferdinand de Saussure.” YouTube, uploaded by DoE-MKBU, 22 June 2012, youtu.be/V7M9rDyjDbA. Accessed 25 June 2025.

---. “Unit 5: 5.3 Derrida and Deconstruction - DifferAnce.” YouTube, uploaded by DoE-MKBU, 22 June 2012, youtu.be/WJPlxjjnpQk. Accessed 25 June 2025.

---. “Unit 5: 5.4 Derrida and Deconstruction - Structure, Sign & Play.” YouTube, uploaded by DoE-MKBU, 22 June 2012, youtu.be/eOV2aDwhUas. Accessed 25 June 2025.

---. “Unit 5: 5.5 Derrida and Deconstruction - Yale School.” YouTube, uploaded by DoE-MKBU, 22 June 2012, youtu.be/J_M8o7B973E. Accessed 25 June 2025.

---. “Unit 5: 5.6 Derrida and Destruction: Influence on other critical theories.” YouTube, uploaded by DoE-MKBU, 23 June 2012, youtu.be/hAU-17I8lGY. Accessed 25 June 2025.